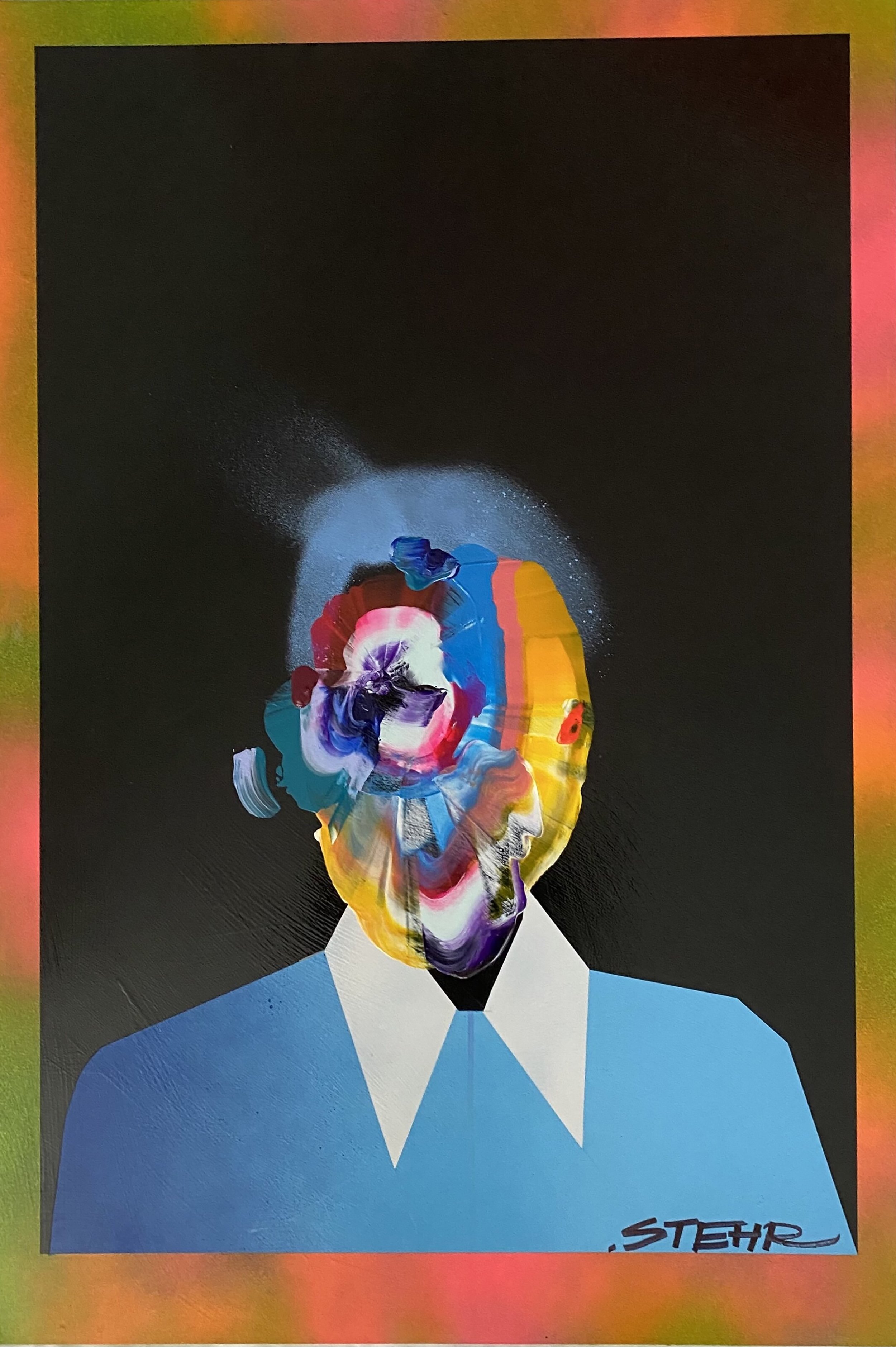

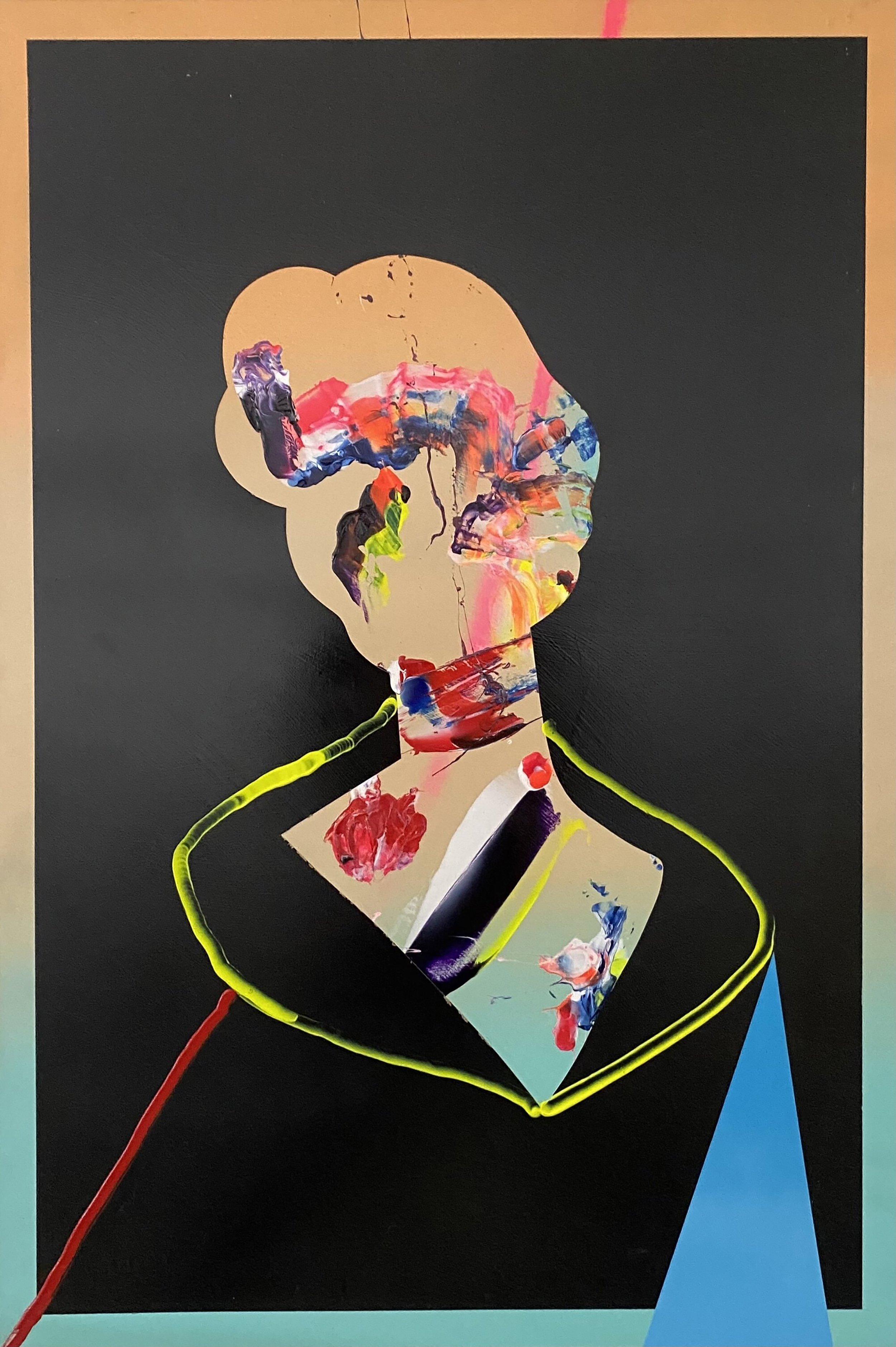

GARETH STEHR

These abstracted figurative paintings pair so well with Diary of a Head Injury (see SM Volume 3) because they are so evocative of confusion, disruption and mental anguish, but the connection is not a superficial coincidence.

Artist Gareth Stehr also suffered a serious brain injury and shared similar experiences to Nick Worthington on both

physiological and psychological fronts during recovery.

While his skating accident was not the only catalyst for this particular phase of his artistic expression, it lends depth and meaning to the technique on a very personal level. He cites the work as being key to his rehabilitation.

“I feel that I am back on top and better than ever. How beautiful and strong the brain is.”

Hailing from Norfolk Island and growing up in Auckland, Gareth then moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career as a professional skateboarder. He began showing at local LA galleries and developed his style as a fine artist. Gareth has had shows across the globe and continues to develop his unique style, painting or creating every day.

Gareth’s style is constantly evolving while he experiments with different medias, including sculpture. He enjoys invoking strong emotions from the viewer using bright, bold colours and the theory behind them.

STREETWISE: Catching up with KEZAM

Kezam started writing graffiti in Melbourne, Australia in 1989. Since then, he has lived and painted in numerous cities, including New York and San Francisco. These days, you might stumble upon his work in Auckland.

Growing up in Melbourne, were you into art as a kid?

I was not really into art, but was interested in lettering and fonts. One of the first books I ever had as a child was on letters, fonts, and how to produce them from a graphic design perspective. In short, it was basically a book of lettering styles with graphic designers in mind. Looking back, I think the first time I saw graffiti, it made sense to me because of my exposure to that book.

I took art and graphic design in high school, but I was not very serious about them as a student, and I never really thought of them as things I would want to marshal into a career. There was a lot of information from the art and graphic design world that became important to the graffiti writing, but I also think graffiti is a world unto itself, one in which you learn “on the job,” so to speak. So, they are related, but distinct, worlds.

What are your earliest memories of seeing graffiti and how were you inspired to begin?

I first saw graffiti when I was about nine or so. My mum and I would pick my dad up from the train station after his work day. While waiting for my dad, the trains would pull up and they would often have graffiti on them. The train station was also covered in graffiti. I appreciated the lettering book, and I think I saw graffiti as an extension of that. As a result, the graffiti didn’t bother me; I liked it.

A few years later, I met an older graffiti writer who lived up the street from me. He showed me the book Subway Art, and explained the basics of graffiti writing culture. He also gave me a marker. It was a Pilot “flow pen.” That exposure

got me more interested, and it was around that time that I started going out and writing. Back then, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, most people had no way of paying for graffiti supplies, and so you had to ‘rack’ or steal paint, ink, markers, and so on. It was a very different world, where you had to make-do with whatever materials were available. These days, there are specialist paint companies, gearing their products toward graffiti writing.

Describe your professional life and its connection to your artistic life?

As a professional, I work as an academic. I see the professional and artistic life as more or less the same thing, or variations on the same theme. They are both creative forms of work, albeit with different audiences. Both require that you know the past if you want to try and do something new or different. They are both dialogic, and both compel you to produce rather than simply consume what others make.

Lets talk about New York. Do you think your art would be different if you hadn’t lived there?

I lived in New York for about seven years, then in San Francisco for a year or so. As most people probably know, New York City was, and remains, the mecca for graffiti. It would be hard to live in New York and not have it impact what you do as a graffiti writer. I think New York had two major effects. On the one hand, it really made me more reflexive about graffiti writing; it made me think about what I wanted to do in the graffiti world, what it was that I could offer, if anything. In New York, there are a lot of very advanced graffiti writers, and it is very hard to stand out. So, it compels you to innovate. On the other hand, I started painting bigger walls with other people and that was important to development.

When you paint larger walls, you really have to think about the whole thing, not just your piece or your letters. How are pieces and background interacting? What is the background to the piece? A lot of graffiti writers just focus on the letters, and try to separate their work from whatever is already on the wall with some simple bubbles. So, graffiti writing often excludes, or doesn’t really treat the background as a serious element to the work. New York changed that for me. The whole wall matters, put the background to use.You finish a piece and step back.

What does that feel like?

It varies. Sometimes it is sheer disappointment. You’ve spent hours on a wall and it just doesn’t look right, or it does not accord with what you thought you were doing. You had a vision, but the finished painting is pretty far removed from that vision. That sucks. But, I guess it motivates you to get back out there and try it again to get it right. Very rarely, there is a sense of satisfaction. You look at the wall, and it more or less coincides with what you were trying to do. But, as I say, that is very rare. Typically, things are somewhere between these two extremes. There are parts of the piece that you feel came out right, but things that you missed. So, the end result is usually ambiguous. But, I think anyone who makes stuff on a regular basis would have this feeling. You are going for something that is elusive, always just out of reach. I think any creative endeavour thrives on such ambiguity though: if you could produce the perfect work, there would really be no need to keep going.

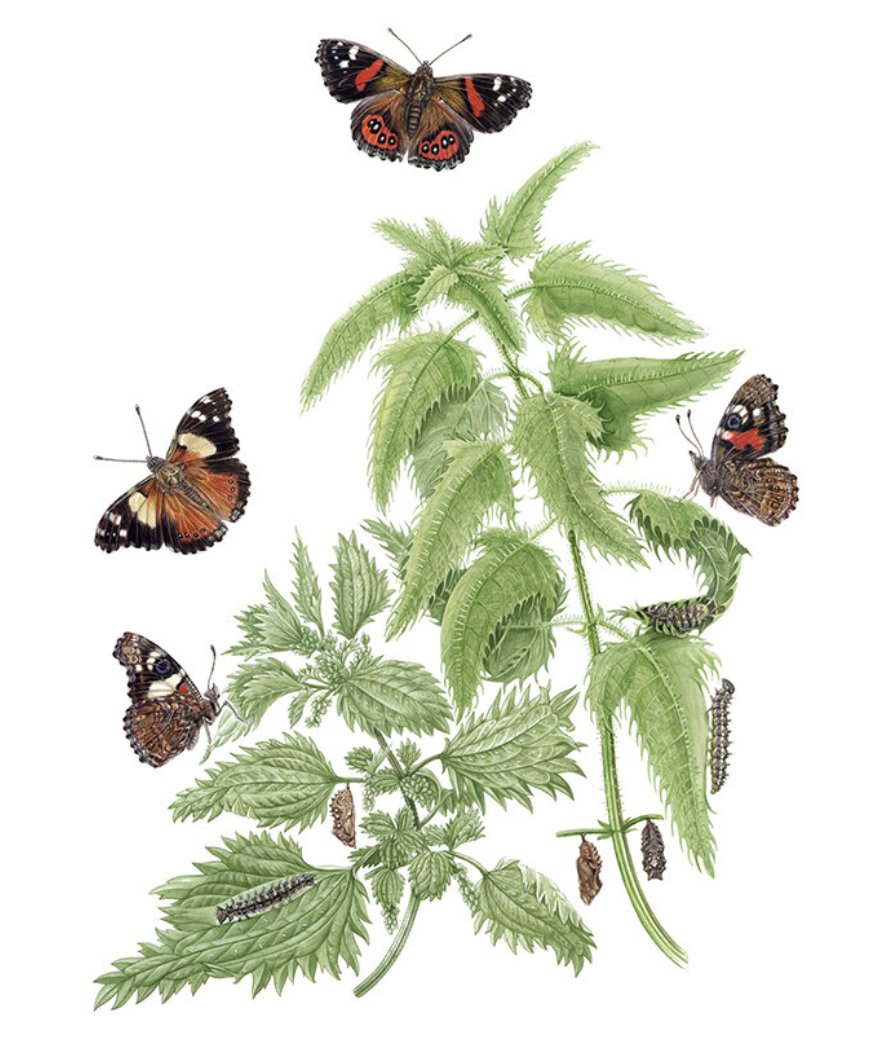

A NATURAL HISTORY: submachine has a beer with erin forsyth

Erin Forsyth’s talent, mixed with 90s hip hop, punk and hardcore flavours saw her illustrating album covers and gig posters, t-shirts and skateboards, but the superficial nature of that work left this sponge for knowledge wanting more.

Tracing the trajectory of Erin’s artistic path over a couple of cold cans in the Mt Roskill winter sun, I discover that it is actually a series of trajectories punctuated by decisive changes in direction. With each reset Erin stowed away all her learnings and strove to go deeper, creating a body of work with a great deal more going on than meets the eye.

Erin’s early work illustrating posters and album covers was fulfilling to a point, but there was a nagging emptiness, a lack of deeper meaning and a desire to produce something more impactful. It was however, a good introduction to commercial work and Erin was creating a following.

Her career is founder on periods of intense learning. A year-long stint at animation school meant 8 hours a day hand-drawing frame after frame in the traditional, pre-digital method. This tedious endeavour was never going to fulfil Erin but there is no doubt the discipline was invaluable. She opened her own graffiti art store, Creep, as a way of immersing herself in that world and learning all she could. “I met a lot of (graffiti) artists. If you meet an artist, you learn from them. And you learn how to be a person in the world.”

“Twelve year old kids from South Auckland would turn up on their bikes and buy 5 caps between them, but I would teach them what the different caps could do. The store was cool. Then it got robbed and it wasn’t cool. So I moved to Australia!”

Erin hung with artists, musicians and writers in Sydney and while it sounds relaxed and bohemian, it was a revelation for her, and another lesson in discipline. These were highly productive people.

“I was used to people who sat about in cafés talking about being an artist, but they weren’t making any fucking work. In Sydney they would be working by 8am every day. The discipline was inspiring and motivating. I learnt how to work.”

Erin’s art matured as she became more technically accomplished. The hard work was starting to pay off and her paintings now seemed a world away from the early poster art. Flora and fauna weave their way through her work and there’s no questioning its beauty. Still, Erin continued to question its importance.

Seven years ago, she changed gears again and found the thread that continues to flow through her work today. A golden thread, laced with meaning and importance. Once again her quest for knowledge kicked in and she studied Environment and Sustainability, including a paper on Ethnobotany, the relationship between plants and people. Here she discovered a disconnect between the scientific community and the knowledge base Maōri had already established over hundreds of years, particularly Rongoā Maōri.

“I think it’s often necessary in life to unlearn what we are taught in school.”

Erin’s natural history and botanical illustration has been steadily gaining recognition for its importance and relevance, but also for its thoughtfulness and the depth of knowledge that backs it up. It’s detailed, painstaking work and the brushes are tiny. To offset this fine, focussed work, there’s a big shed in the back yard where she can go large on a big canvas. Erin’s work resides in the collections of the Auckland Museum and also at The Beehive in Wellington.

There’s now a sense of real purpose for Erin and she seems to be on a mission to carefully document all of our native plants and animals and in the process expand our understanding of the land we inhabit.

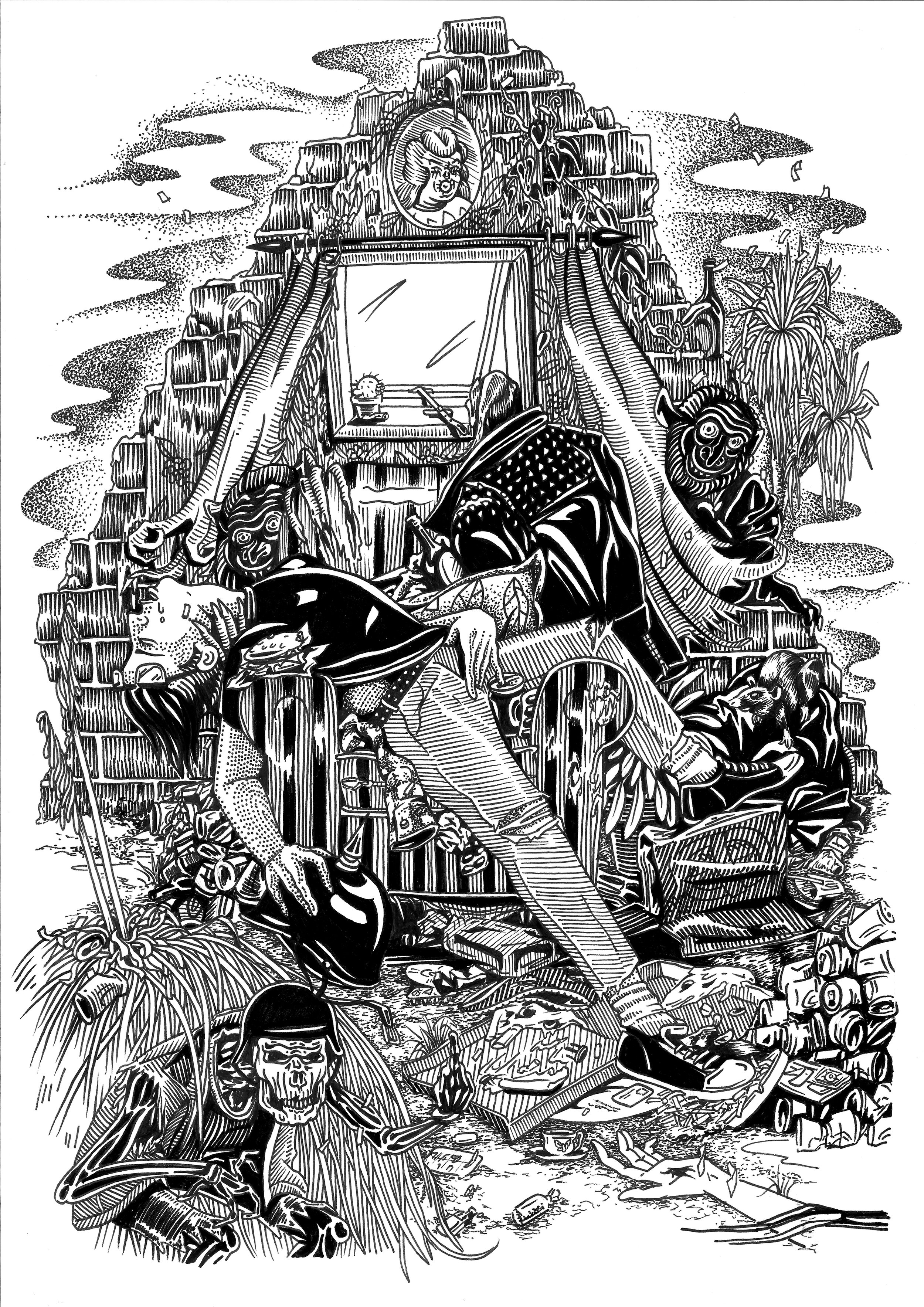

HUMAN RENDER ENGINE: THE UBER-TALENTED GREG BROADMORE

WĒTā WORKSHOP’S TALENTED CONCEPT ARTIST ON PROCESS AND PATIENCE.

When Greg Broadmore sent his portfolio to Wētā Workshop’s Richard Taylor he was hired immediately.

Greg has worked on King Kong, Avatar, Tintin and The Chronicles of Narnia, to name a few, and was lead designer on Neil Blomkamp’s District 9. For a comic fan who loves to draw, it would have been a bit of a shame if Greg had become a dentist or a fishmonger. Destiny has done its thing and Greg is where he belongs.

Asthma precluded Greg, as a child, from the kind of outdoor activities that most kids partake in. Even as a child, you fill your days how you can and Greg’s world was comic books and drawing. His grandad worked at the paper mill in Whakatane and used to bring home stacks of comics, unsold at newsagents and with their covers torn off, destined for pulping. This may have helped fuel Greg’s imagination trying to figure out what the coverless comics were about.

Drawing people and animals is not easy but Greg can do it without reference. He puts that down to simply growing older and therefore having a deeper understanding of how the world around him works. You can tell from his seemingly innocuous Instagram posts that he is a keen observer of things and this, layered over his technical understanding of anatomy, means he doesn’t have to think too much about it. His current personal project is a series of graphic novels which he teases out in small doses on social media, and it looks amazing. He works a couple of days a week at Wētā Workshop but the rest of his time he is writing, drawing and rendering the comic. The sheer volume of work involved in a graphic novel means long hours and, at times, a shift in the circuitry of the brain to facilitate that.

That is certainly true of the colouring phase, where Greg likens himself to a piece of high-end rendering software. In this state he can listen to podcasts and audiobooks or any other vocal background noise without any distraction. He switches off certain parts of his brain and is able to just render away.

The pencil stage, which comes first, is a different story, and requires much more focus. Music is fine (ideally without lyrics) but any dialogue or human chatter can break the rhythm of the storytelling. The analytical and reasoning parts of Greg’s brain are firing on all cylinders as he sketches the novel out frame by frame, page by page, composing it like a movie director. Every frame is worked out on the basis of narrative and visual impact, keeping the reader engaged and also ensuring they can follow the action in an immersive way. Ironically, Greg can turn out the pencil pages much faster than the renders.

Frames are composed in much the same way as filmakers do with storyboards; roughly sketched to work out camera angles and moves or more rendered versions to pitch the story to outside parties. In a sense, Greg has come full circle, from his comic-mad childhood to a cinematic world where that visual storytelling was invaluable and to now producing his own comics.

Greg’s care and attention to detail means that there is no quick way to produce this work and he has not set himself any deadlines to finish the series. Even if a frame is only going to be tiny on the printed page he will still work on it full screen.

“I just can’t help myself.” he laughs.

“I feel bad at the end of the week when I haven’t done enough artwork, and I am trying to figure out shortcuts.

Some people are really great at it. I love it when an artist almost didn’t care about a certain brushstroke but it still feels good and it still gets across the idea. That’s something I’m always trying to chase. Speed and beauty. It’s a weird thing to be doing in this day and age with all the high-end rendering engines available. I’m doing it the brute force way.

I don’t know what it is but it’s that flow-state feeling where you get into the zone and lose yourself. That is its own enjoyment. It might not be the practical way to do it any more but it certainly feels good. Modelling and lighting engines are fantastic but with art style, it’s all the idiosynchrasies that make you you. They turn up in the art, and that becomes your style.

I learnt how to paint in the traditional method, using acrylics and oils, but once I started at Weta Workshop using Photoshop, I massively preferred it. I think I have a painterly style because I learnt traditionally but I love Photoshop. You don’t have to wait for the fucking paint to dry!”

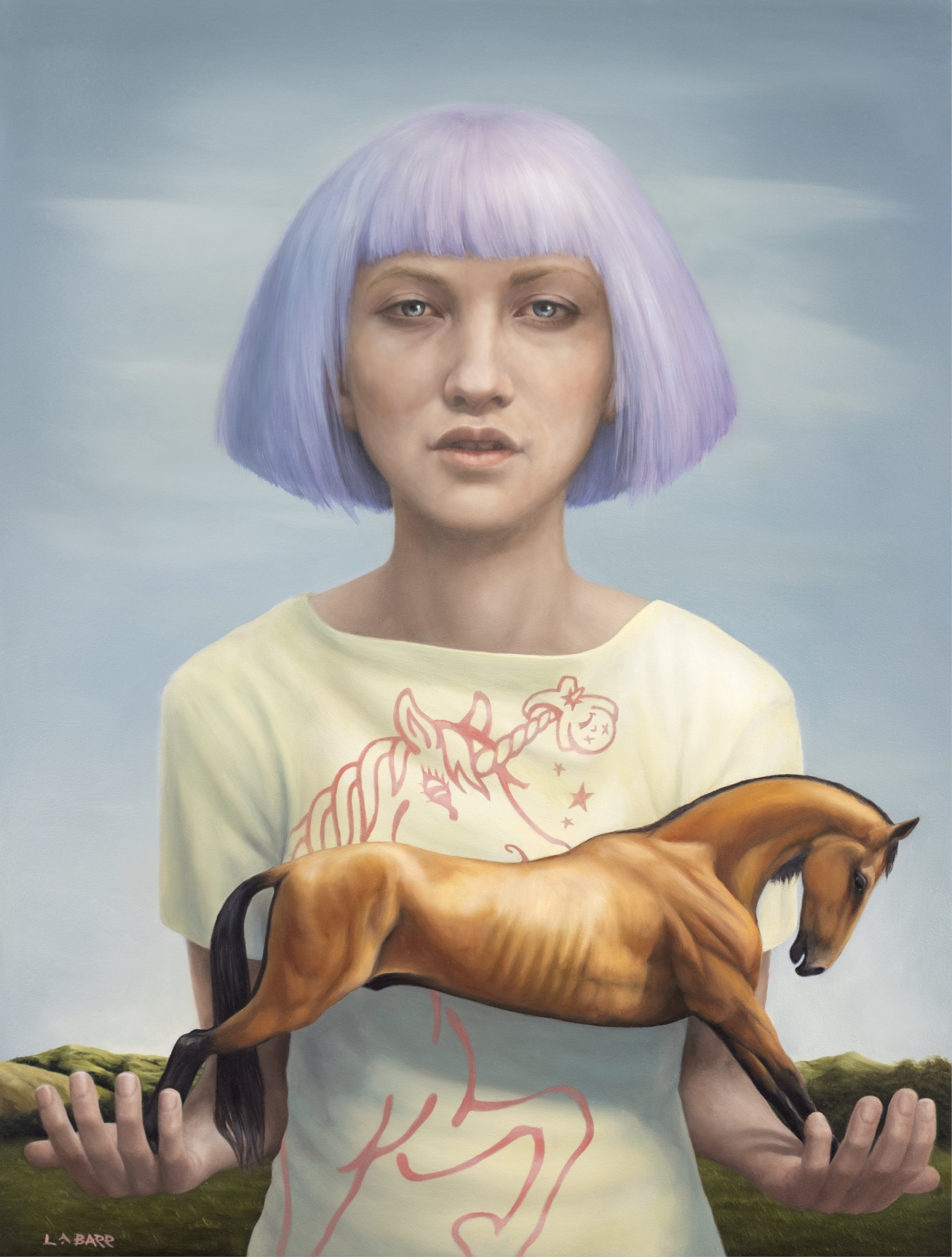

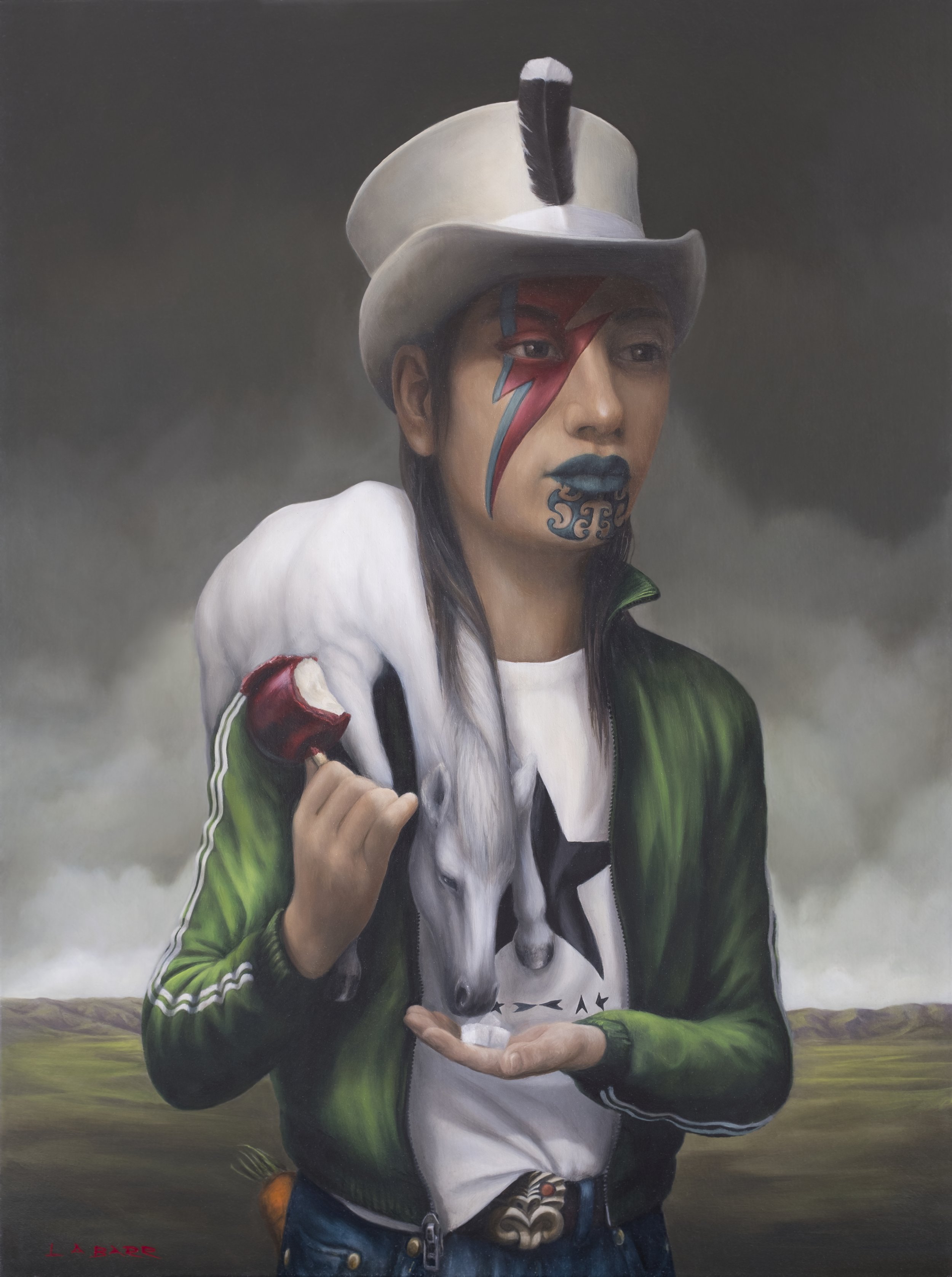

open your eyes and dream: The calming, contemplative, magnetic and ever-so-slightly haunting paintings of Liam Barr

When we begin to emerge from a deep slumber there’s often a tantalising, desperate moment where it seems possible to re-enter a dream. Liam Barr is here for you, holding the door ajar, calling out to guide you back from the harsh reality of the waking world. Welcome to the simultaneously surreal and strangely familiar.

Liam hails from Scotland, though moved as a young lad, with his family, to New Zealand in the 1970s. His father also painted and was able to impart that vital energy to ignite Liam’s interest in art. A childhood split between the bleak ‘best stay indoors’ weather of Scotland and the unfamiliarity of New Zealand meant Liam became fully immersed in drawing and creating.

“I knew, even then, that at some point I was going to be an artist, if I could ever wrangle it.”

His tertiary studies in illustration and computer graphics, and his early working life as a graphic designer provided real-world discipline and the security to, when the time was right, transition over to dedicating himself to full time painting. Liam had imagined that might be much later in life but he and his partner were able to juggle things and make it work.

Pop surrealism and low brow art was a big influence as Liam developed and grew as a painter, and he cites Mark Ryden as significant inspiration, not only stylistically, but in terms of what a painter could be. Ryden’s work bent the ‘rules’ in the context of a fine art aesthetic and, as Liam found, pouring over Juxtapoz magazines back in the day, there really aren’t any rules.

Those early influences were liberating and allowed Liam to ask his own questions, of himself and his painting, and then let ‘style’ fall where it may. These questions are explored through each series of paintings and the outcomes for each series are unique, to the point where Liam could be said to be continually evolving, or at least re-setting.

Painting in a series of explorative blocks of time sounds fairly straightforward. A few weeks in this direction, a few weeks in that. No. Liam’s discipline and patience is such that each individual painting can take two or three months. I would encourage you to visit his website and look through each series, to give a sense of the time involved, and also how his approach changes for each.

Liam has generously allowed me to curate a small gallery for you here on these pages, a taste of his talent and the dream-like qualities that weave their way through his work. I was surprised when he told me that, for the most part, the people are fictitious. I imagined Liam having a friend or colleague, or a patron perhaps, sitting for him. Maybe taking a few photographs for when the model goes back to his or her daily life? Liam simply makes the characters up, from nothing but his own experience as a painter.

This struck me as a critical factor in the nature of his work and its surreal inclination. In dreams we often see people we know, but can’t recognise. “We were being chased by a giant avocado and you were you, but your face was different...” so perhaps the surreal, semi-real and the real come together in these paintings which Liam created using his subconscious as a guide.

STREET appeal: a drive-by encounter

Driving past a long, featureless wall in the Avondale sunshine, I caught sight of an artist laying down the first rough strokes of a piece of typography. Apart from this small pocket of activity, the wall was blank and untouched, painted a depressing shade of council green and it completely dwarfed the artist.

As it transpired, I had to venture out that way again the next day, so I was looking forward to seeing how far that

lonely soul had got with their little graphic on that massive wall. I guess Sunday morning is as good a time as any to have your mind blown. Not only was the artist gone but the entire wall had been covered from footpath to sky in a pulsating, eyeball-melting typefest.

The most dedicated graffiti artists stick to their guns and get the job done, and whoever it was I’d seen the day before clearly wasn’t alone for too long. A small community of talent had banded together to create a stunning colab piece for the benefit of the wider community, and I, for one, wanted to say thank you.

Big ups to Berst, Fluro, Diva, Burns, Hoaks, Sef, Race, Cesr, Nvade, Dreto, Pills, Famesta, Haser and Revos.